We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

When former college president Steve Leath took the reins of the Council to Advance Hunting and the Shooting Sports in 2021, and demanded that data be used to guide the success of hunter-recruitment programs around the country, he expected the sporting goods industry would be delighted.

“It seemed obvious to me that if we could show we were successful in getting more people into hunting and shooting, whether through recruitment or reactivation, and then retained them, then the industry would recognize and reward our role in creating more customers,” says Leath. “That hasn’t happened.”

Instead, as R3 efforts (recruitment, retention of existing hunters, and reactivation of lapsed hunters) have been established by nearly every state wildlife agency and many non-profit conservation organizations, deep involvement by the firearms, ammunition, and sporting goods industry has been largely absent.

The reasons, according to sources in every sector working to create more hunters in America, include poor and sporadic communication, differing expectations, and soul-sucking bureaucracy and agency oversight that impedes quick and decisive action. But many sources point to a cultural and philosophical divide between the for-profit world of industry and what one industry leader called the “wishful-thinking” world of hunter recruitment.

“I come from a background in business,” said the leader, who asked not to be named so they could speak candidly. “Across R3, not only are there no clear plans, there aren’t even any specific goals. What are the KPIs [key performance indicators]? How do we gauge success? You can’t just say we want to sell more hunting licenses and have more participation. Those aren’t goals. Those are dreams. No business would be okay with that.”

But creating hunters isn’t a quick or linear progression, argue many R3 practitioners. First comes engagement, introducing the concept of hunting to people who may not have a family or cultural connection to the activity. Next comes participation, either in a field event or a mentored hunt. Durable recruitment programs next build social structures to support the new hunter, and finally — if all the efforts are successful — a beginning hunter might achieve escape velocity and perpetuate those activities without assistance. In the best-case scenario, the former apprentice hunter in turn becomes a mentor, introducing new people to the activity.

In most cases, there’s significant “leakage” between each of those steps, to the degree that only a handful of prospective hunters actually become fully activated hunters. And completely recruiting a new hunter often takes years, says Eric Dinger, whose former company Powderhook was an early champion of matching beginning hunters with experienced mentors.

“It’s a hard sell to ask a company today to invest in a program that might produce a customer three to five years down the road,” says Dinger, who has since left the industry. “I’d also observe that the hunting industry is divided between small companies that don’t have the kind of money to make meaningful donations to R3, and larger companies that are trying to maximize profits in order to make quarterly targets, or are owned by private-equity firms that aren’t known for their support of long-term initiatives.”

Still, many companies haven’t made even tiny investments in hunter education and recruitment. DeAnna Bublitz is the founder of DEER Camp – MT, a Montana-based gear lender that helps reduce barriers to hunting by loaning backpacks, optics, outerwear, and other hunting gear to beginning hunters. Bublitz has solicited many brands in the hunting industry for contributions but has either received form rejection letters or has been ghosted. She relies on second-hand gear from friends and neighbors to stock her lending library.

Bublitz, along with many other R3 practitioners, expected that brands would be eager to present their products to new hunters, which in DEER Camp’s case include many non-traditional hunters. The thinking goes that if a beginning hunter has a positive experience using a certain rifle, camouflage pattern, or optic, that they will then gravitate to those brands later on out of allegiance and brand recognition.

But Bublitz observes that many brands participate in hunter recruitment programs, but not to broaden participation. Instead, it’s “more as an ‘organic’ marketing strategy. Cynically, companies seem to focus on groups that either have a very active social media presence or can fulfill additional corporate initiatives. Those corporate motivations don’t necessarily build strong relationships” or lifelong customers.

That hasn’t been the experience of Academy Sports + Outdoors, which has partnered with state wildlife agencies in the Southeast on hunter and angler recruitment initiatives, often providing discounts at Academy stores to new license buyers or incentivizing lapsed hunters and anglers to buy licenses.

“We can’t speak for other sporting goods retailers, but supporting R3 efforts has been important to Academy,” says public relations manager Shane Carlisle. “Support of R3 organizations has allowed us to support our local communities through product donations and sponsorships while allowing us to reach new customers who share our passion for the outdoors.”

In other words, R3 has been a reliable pipeline that delivers new customers to Academy stores.

In between the industry and the customers are state wildlife agencies, which have mixed success in connecting the two, says Jenifer Wisniewski, who directed the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency’s special projects and outreach programs, including its R3 initiatives. Wisniewski, now chief marketing officer for the National Deer Association, says agencies often don’t know how to communicate effectively with the private sector.

“If you ask a state fish and wildlife agency how many new hunters they could create with $1 million they would have no idea,” she says. “How much does a new hunter cost to make? No clue. We haven’t gotten good enough at R3 to make a good business pitch at least programmatically for our ‘learn-to-hunt’ type efforts. The best a business could do is give us equipment that we would use to teach people. But a state agency is prohibited by procurement laws and other policies from saying that company’s equipment is any better than any other equipment.”

What remains to a business that wants to support R3 efforts is sponsorship: donating precious cash to an agency partner or program. But which programs should companies support? What return can they expect for that investment?

“This becomes feel-good marketing where company X is a ‘partner in conservation’ to the agency,” says Wisniewski. That’s a hearty expression of a durable relationship between a state agency and a business, but it’s not necessarily profitable. “Marketing folks in any industry aren’t going to want to spend their money on this when they can place direct-to-consumer ads that give a measurable ROI.”

But R3 programs in many states are still in their infancy. As programs mature, scale up, and start to accumulate data, they’ll be better able to prove their value to not only agencies but to the wider community. Many R3 practitioners are eager to see results of the latest national report on hunter recruitment programs, due to be released at this summer’s National R3 Symposium in Mobile, Alabama. They hope it shows that nascent R3 efforts are, after a few years of incubation, finally making a statistically meaningful difference.

Hunter Participation Data

Why does hunter recruitment matter, in the first place? Because the number of hunters in America is dropping as measured both by participation and as a percentage of the population. Hunters in America are not only getting older, they also tend to be disproportionately white, male, and rural, all demographic categories that are getting smaller as America becomes more urban and diverse.

“We had a spike in hunting during the height of the Covid pandemic, as people either discovered the outdoors for the first time or renewed latent hunting traditions, but overall the trend line is negative,” says Leath, whose Council to Advance Hunting and the Shooting Sports is one of many entities that are institutionalizing the precepts of R3. Not only have most states added R3 coordinators and created outreach programs in the last couple years, but member-based groups such as Pheasants Forever and Backcountry Hunters & Anglers are also active in the space. All these groups have more resources at their disposal. In 2020 Congress passed the Modernizing the Pittman-Robertson Fund for Tomorrow’s Needs Act. That law allows states to use P-R funds, taxes collected on the sale of every gun and box of ammunition sold in America, to market and promote hunting and shooting and to fund recruitment efforts.

The reason so much energy animates R3 efforts is because fewer hunters means less financial support for state wildlife agencies, fewer advocates for habitat and access initiatives, and fewer voters to support traditional activities like predator hunting and trapping, which are increasingly at odds with changing American wildlife values. And, presumably, fewer hunters also means a decline in sales for companies that make hunting gear.

These long-term threats to hunting participation tend to get the attention of companies whose futures are tied to having robust populations of Americans who buy deer licenses and deer rifles. But one reason sporting goods manufacturers aren’t lining up to contribute to hunter-recruitment efforts may be because they don’t need to be.

Turn Toward Shooters to Make New Hunters

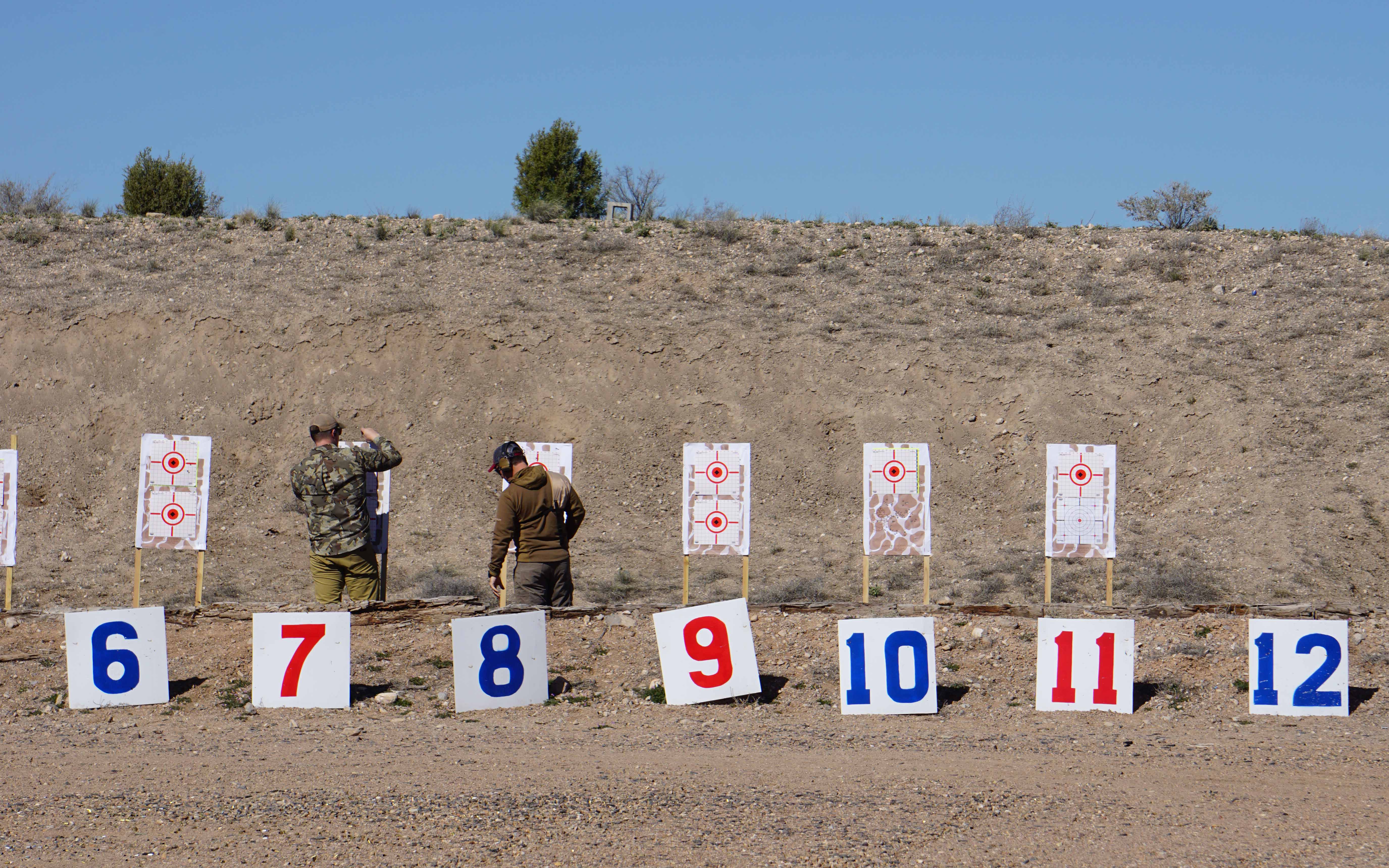

While the number of hunters is in a long-term slide, the number of recreational shooters in America has never been higher. If state agencies are struggling to sell hunting licenses, firearms manufacturers are enjoying a steady boom. Americans bought nearly 60 million guns during the pandemic, and 7.5 million Americans bought their first gun in the two-year period from 2019 through 2021.

All those new gun owners, in addition to the 80 million incumbent shooters who send many millions of rounds downrange, means many gun and ammunition makers are so busy meeting market demands that they don’t have the capacity to focus on R3.

Besides, say some insiders, the process of converting a new gun owner into a lifelong shooter is much shorter and easier than converting a hunter education student into a lifelong hunter.

“It’s a lot easier to be a self-taught shooter compared with a self-taught hunter,” says the unnamed industry leader. “You spend enough time in the basement with your new AR and a YouTube video, and you can figure out how to strip down and put back together your gun blindfolded. It’s harder to do with hunting. Even with the proliferation of information out there, there’s that first step of ‘cut out that butthole and get the guts out.’ That’s a lot harder to learn by yourself in your basement.”

Jon Zinnel, conservation senior manager at Vista Outdoor, which includes as its brands Federal, Remington, and CCI ammunition, says that if you’re measuring success by moving products, supporting shooting sports has a more positive return on the investment to companies than supporting hunting programs.

“From an industry perspective, an active shooting participant is a better investment,” says Zinnel. “You have a hunter shooting a box of ammo per season versus a shooter who might go through 10 cases of ammo per season. A hunter buys one riflescope, but a shooter might buy a scope for every rifle, plus a spotting scope.”

Zinnel says there’s abundant evidence that beginning shooters who are introduced to field days — scholastic clay target programs, precision rimfire competitions, or even Archery in the Schools sessions — are likely to pursue shooting sports on their own.

“I’d argue—and this is just my anecdotal observation — that it’s easier to take a shooting enthusiast and turn them into a hunter than it is to find a hunter from the general population,” says Zinnel. “So maybe the R3 community needs to start with recreational shooting programs. Start with shooting clay pigeons and then transition into pheasants. Start with Archery in the Schools and then transition into bowhunting for deer.”

Zinnel’s company is the largest single contributor to Pittman-Robertson funds, those taxes on guns and ammunition that fund wildlife management, habitat, and salaries for, say, game wardens. The money trail, which starts with gun and ammunition makers that increasingly don’t produce products primarily designed for hunters, supports a heightened emphasis on recreational shooting by state agencies and other R3 practitioners.

Thanks to both the P-R Modernization Act and the 2019 Target Practice And Marksmanship Training Support Act (TARMARK Act), it’s easier than ever for states to create shooting facilities that perpetuate the cycle of shooters buying guns and ammo that fund the Pittman-Robertson account, which then helps pay for more shooting facilities. The TARMARK Act allows state agencies to supply just 10 percent of funds for a shooting range; the remaining 90 percent comes from the P-R fund.

“You literally couldn’t create a more successful recruitment structure,” says the unnamed industry leader. “TARMARK provides essentially free money for states to build shooting ranges. But you’d be amazed at the state agencies who refuse the funds and say that wildlife agencies have no business building shooting ranges. Minnesota and Illinois are two that come first to mind. This despite the fact that over 80 percent of the P-R funding for both those agencies comes from recreational shooters. That blows my mind.”

Meanwhile, across their borders in both Wisconsin and Ohio, state agencies are building more ranges all the time, including those with classrooms and hunting grounds. Other states, like Missouri, have tried to measure the overlap between hunters and shooters as they try to serve both populations at shooting ranges and wildlife management areas, where unsupervised recreational shooting often takes place.

The R3 leader stresses that state agencies’ slow recognition of both hunter recruitment efforts and recreational shooter contributions is understandable.

“You have to remember, state agencies don’t talk to either new hunters or to shooters,” he says. “Who comes to their public meetings? Who engages in department policies and regulation changes? Existing hunters who have skin in the game. A regional wildlife manager is going to pay way more attention to the couple of loudmouths who want to run their dogs on a wildlife management area than to the hundreds of people who would benefit from a local shooting range. Until agencies hear from constituencies that don’t typically show up at meetings or submit comments, they’re not likely to change their priorities, which is why R3 efforts are under-resourced, under-valued, and misunderstood by agency leaders.”

“And yet, you still hear ‘Hunters Pay for Conservation.’ There are even bumper stickers to that effect,” says the R3 leader. “But that hasn’t been the case for at least 10 years. Recreational shooters pay for conservation, and most of them are still waiting to see some return on their investment.”